It was my second visit to Passchendaele and it was no less emotional.

The first visit to the region had been in the early 2000s escorting my parents first to Normandy and the WW2 D-Day region of Northern France and then onto the WW1 sites in and around the Somme region of France and also into neighbouring and Belguim.

The second visit in September, 2013 was much the same and this time in the company of my brother, Steve and his wife, Sally (Sal to her friends).

The second visit in September, 2013 was much the same and this time in the company of my brother, Steve and his wife, Sally (Sal to her friends).

To any Australian, towns such as Passchendaele in Belguim and Ypres a short distance away in France along with Gallipoli in Turkey are synonymous with the ANZACS.

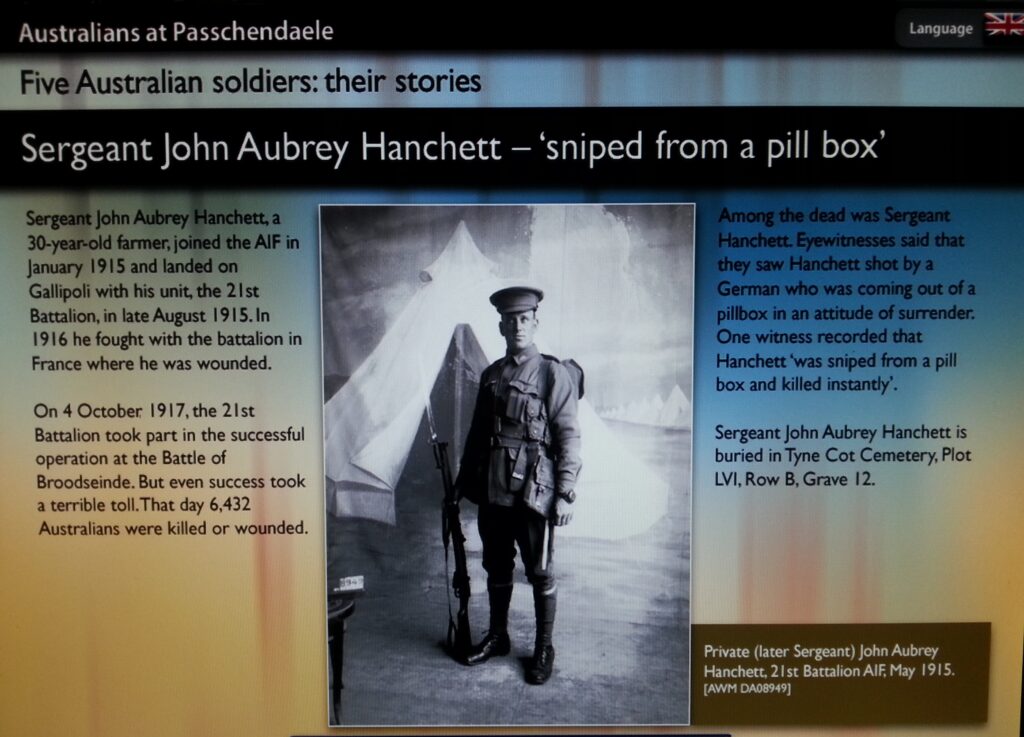

And for the majority of Australians they are somewhat like a magnet as firstly, you want to pay your respects, and secondly but no less important, you want to try and experience what those young Australians endured by walking the battle grounds, reading each and every commemorative plaque, walking through the doors of each museum and finally walking down rows and rows of gravestones and noting their average age was either 18, 19, 20, 21 or 22 years.

The two towns of Passachendaele and Ypres are just 13 kilometres apart and in driving between the two towns you pass by many, many reminders of the events of over a century ago and while it may just be a 20-minute direct drive, it can take you almost all day if you stopped at every monument, plaque and museum.

In the First Battle of Ypres (19 October to 22 November 1914), the Allies captured the town from the Germans.

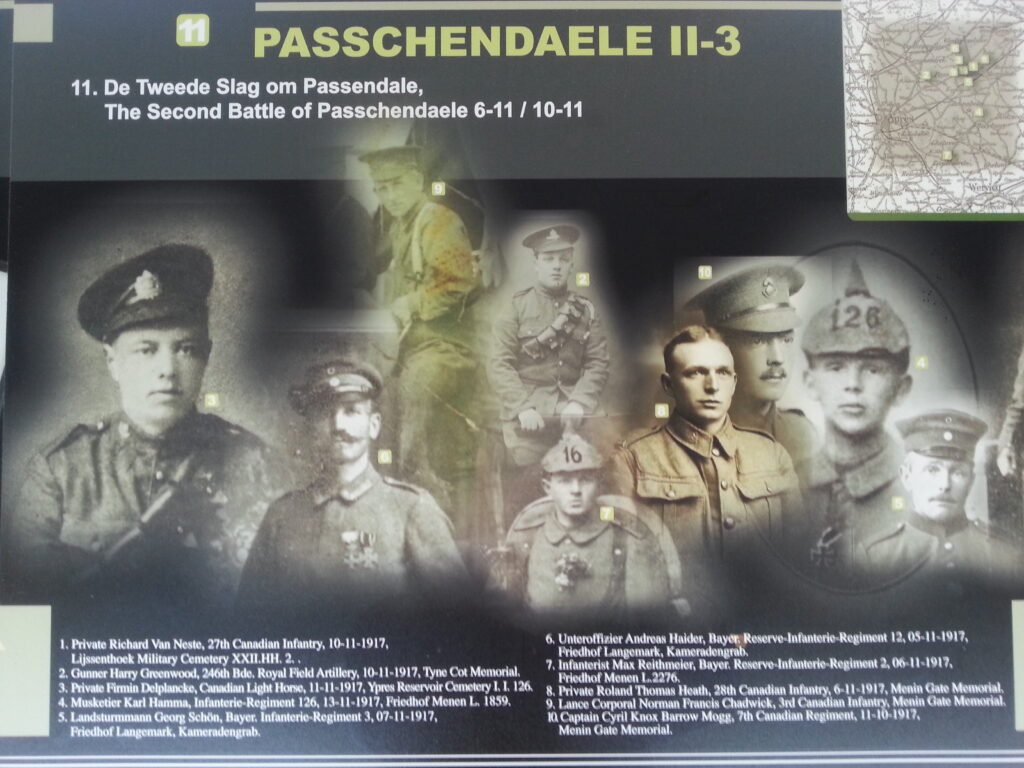

Of the battles, the largest, best-known, and most costly in human suffering was the Third Battle of Ypres (31 July to 6 November 1917, also known as the Battle of Passchendaele), in which the British, Canadian, ANZAC, and French forces recaptured the Passchendaele Ridge east of the city at a terrible cost of lives.

After months of fighting, this battle resulted in nearly half a million casualties to all sides, and only a few miles of ground won by Allied forces. During the course of the war the town was all but obliterated by the artillery fire.

World War I, sometimes called the ‘Great War’, lasted four years, from 4 August 1914 until 11 November 1918. Initially it was a war between two sets of alliances: the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary and their allies) and the Triple Entente (Britain, France and Russia) and their allies, including the member countries of the British Empire, and the USA, which entered the war in 1917.

The war began soon after the assassination of the heir to the Austrian throne by a Serbian nationalist. Austria threatened to punish Serbia, an ally of Russia. Russia threatened Austria. Austria, in turn, appealed to Germany. Germany struck first by declaring war on Russia and its ally, France.

When Germany invaded Belgium, Britain entered the war on the side of Russia and France. The date was 4 August 1914.

The war was fought on a number of fronts. In Europe, the Western Front was in France and Belgium. The Eastern Front involved Russia and Austria-Hungary. Africa was another front because of colonial possessions on that continent, and after Turkey entered the war on 1 November 1914, the Middle East became another theatre of war.

An estimated 10 million lives were lost in the war and the dominance of trench warfare in Europe resulted in dreadful suffering for all troops. From 1917, the Allied Powers (the Triple Entente and its allies) began to overcome the Central Powers, and the battle at Amiens in June 1918 launched the victorious Allied offensive.

At 11am on the 11th November 1918 the Armistice was signed, signaling the defeat of the Central Powers.

On 18 June 1919 the peace treaty, the Treaty of Versailles, was signed and the League of Nations established. Under the terms of the treaty Germany was compelled to pay reparations for its actions during the war.

Australian involvement in World War I

Although the theatres of war were very distant from Australia, its membership of the British Empire ensured that there was strong (although not universal) public support for involvement in the war. In 1914, Australia’s Prime Minister, Andrew Fisher, immediately promised Australian support for Britain ‘to the last man and the last shilling’.

The Australian population in 1914 was less than five million. A summary of the numbers of those who served and of the numbers of deaths and other casualties makes it clear that Australia made a major sacrifice for the Allied war effort.

Numbers involved:

Enlisted and served overseas: 324,000

Dead: 61,720

Wounded: 155,000 (all services)

Prisoners of war: 4,044 (397 died while captive)

(Source: Australian War Memorial at http://www.awm.gov.au/)

The Anzacs

Australian involvement in World War I is synonymous with the legend of the Anzacs (ANZAC = Australian and New Zealand Army Corps). The name became famous with the landing of the Corps on the Gallipoli Peninsula, Turkey on 25 April 1915. It was the first military engagement in which significant numbers of Australians fought and died as Australian nationals.

The Anzacs were part of an Allied campaign against the Turks to control the Dardenalles and thus open the way to Constantinople and Eastern Europe. This engagement ended with the evacuation of Australian troops on 19 – 20 December 1915.

The Gallipoli campaign resulted in the disgraceful deaths of 7,600 Australians and 2,500 New Zealanders and the wounding of 19,000 Australians and 5,000 New Zealanders.

Much of the blame for so many needless deaths was down to British blundering. The British command failed in landing the troops at the right location, they failed to fully research the terraine and they grossly misunderstood the tenacity of the Turkish troops.

Despite the defeat, the legend attached to the heroism, comradeship and valour of the soldiers, stretcher-bearers, medical officers and others involved remains a source of Australian pride and national identity.

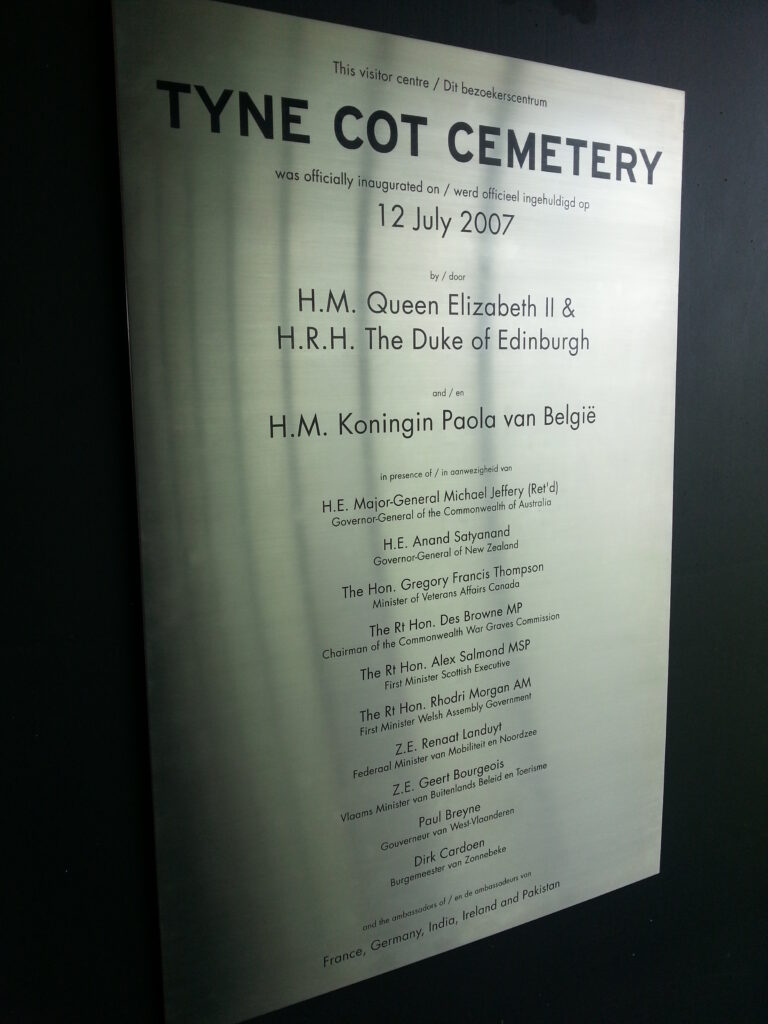

Tyne Cot Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery

The name “Tyne Cot” is said to come from the Northumberland Fusiliers, seeing a resemblance between the many German concrete pill boxes on this site and typical Tyneside workers’ cottages (Tyne cots)

Tyne Cot Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery and Memorial to the Missing is a Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) burial ground for the dead of the First World War in the Ypres Salient on the Western Front. It is the largest cemetery for Commonwealth forces in the world, for any war. The cemetery and its surrounding memorial are located outside Passchendale, near Zonnebeke in Belgium.

On 4 October 1917, the area where Tyne Cot CWGC Cemetery is now located was captured by the 3rd Australian Division and the New Zealand Division and two days later a cemetery for British and Canadian war dead was begun. The cemetery was recaptured by German forces on 13 April 1918 and was finally liberated by Belgian forces on 28 September.

After the Armistice in November 1918, the cemetery was greatly enlarged from its original 343 graves by concentrating graves from the battlefields, smaller cemeteries nearby and from Langemark.

Entrance to Tyne Cot Cementary – It is the largest cemetery for Commonwealth forces in the world, for any war. The cemetery and its surrounding memorial are located outside Passchendale, near Zonnebeke in Belgium.

The Cross of Sacrifice that marks many CWGC cemeteries was built on top of a German pill box in the centre of the cemetery.

The cemetery grounds were assigned to the United Kingdom in perpetuity by King Albert I of Belgium in recognition of the sacrifices made by the British Empire in the defence and liberation of Belgium during the war.[5] The cemetery was designed by Sir Herbert Baker.

The Cross of Sacrifice that marks many CWGC cemeteries was built on top of a German pill box in the centre of the cemetery, purportedly at the suggestion of King George V, who visited the cemetery in 1922 as it neared completion.

The King’s visit, described in the poem The King’s Pilgrimage, included a speech in which he said:

We can truly say that the whole circuit of the Earth is girdled with the graves of our dead. In the course of my pilgrimage, I have many times asked myself whether there can be more potent advocates of peace upon Earth through the years to come, than this massed multitude of silent witnesses to the desolation of war.

— King George V, 11 May 1922

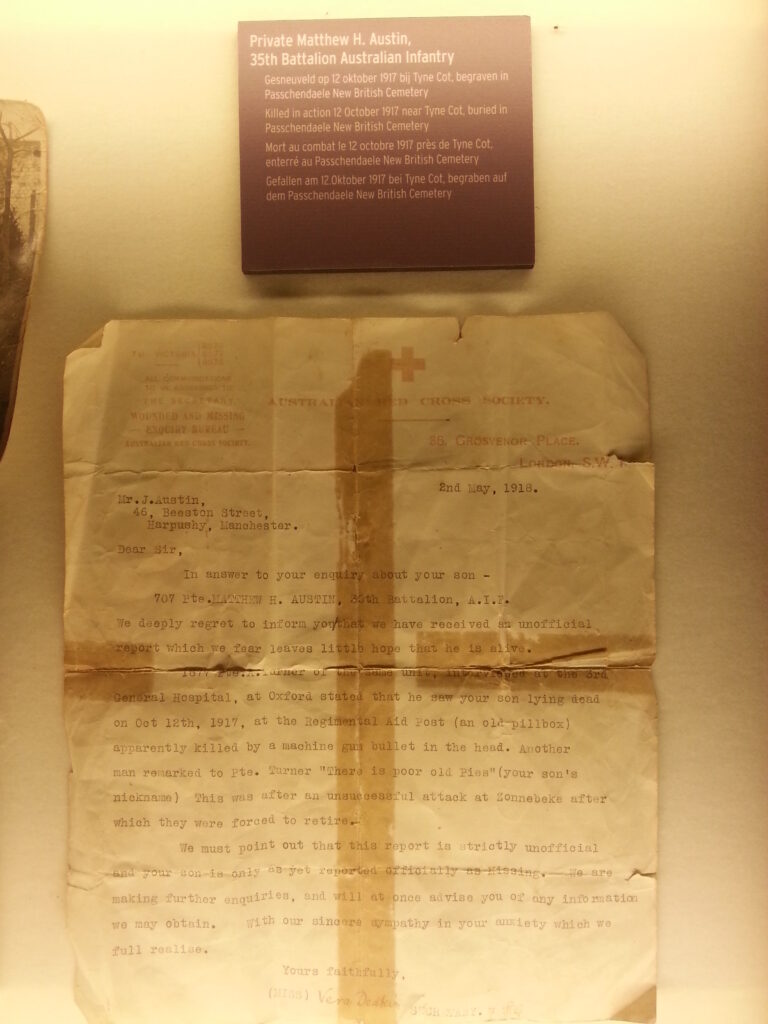

Notable graves

The cemetery has several notable graves and memorials, including the grave of Private James Peter Robertson (1883–1917), a Canadian awarded the Victoria Cross for bravery in rushing a machine gun emplacement and rescuing two men from under heavy fire. He was killed saving the second of these men on 6 November 1917.[1]

Two Australian recipients of the Victoria Cross buried in the cemetery are Captain Clarence Smith Jeffries (1894–1917), and Sergeant Lewis McGee (1888–1917). Jeffries led an assault party and rushed one of the strong points at the First Battle of Passchendaele on 12 October 1917, capturing four machine guns and thirty five prisoners, before running his company forward again. He was planning another attack when he was killed by an enemy gunner. On the same day, McGee, who had earned his decoration eight days earlier at Broodseinde, was killed charging an enemy pillbox in the same battle.

Also at Tyne Cot, behind the Cross of Sacrifice which was constructed on top of an old German pillbox in the middle of the cemetery, there are 4 German graves, buried alongside Commonwealth graves. These graves are of men that were treated here after the battle, when the pillbox underneath the main cross was used as a dressing station for wounded men.

Tyne Cot Memorial to the Missing

The stone wall surrounding the cemetery makes-up the Tyne Cot Memorial to the Missing, one of several Commonwealth War Graves Commission Memorials to the Missing along the Western Front. The UK missing lost in the Ypres Salient are commemorated at the Menin Gate memorial to the missing in Ypres and the Tyne Cot Memorial. Upon completion of the Menin Gate, builders discovered it was not large enough to contain all the names as originally planned.

They selected an arbitrary cut-off date of 15 August 1917 and the names of the UK missing after this date were inscribed on the Tyne Cot memorial instead. Additionally, the New Zealand contingent of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission declined to have its missing soldiers names listed on the main memorials, choosing instead to have names listed on its own memorials near the appropriate battles. Tyne Cot was chosen as one of these locations.

Unlike the other New Zealand memorials to its missing, the Tyne Cot New Zealand memorial to the missing is integrated within the larger Tyne Cot memorial, forming a central apse in the main memorial wall. The inscription reads: “Here are recorded the names of officers and men of New Zealand who fell in the Battle of Broodseinde and the First Battle of Passchendaele October 1917 and whose graves are known only unto God”.

The memorial contains the names of 33,783 soldiers of the UK forces, plus a further 1,176 New Zealanders.

Three British Army Victoria Cross recipients are commemorated here:

- Lieutenant Colonel Philip Bent (1891–1917)

- Corporal William Clamp (1891–1917)

- Lance Corporal Ernest Seaman (1893–1918)

Other notable persons commemorated include:

- Lieutenant Allan Ivo Steel, English first-class cricketer.

- Lieutenant David (Dai) Westacott, Welsh rugby international.

- Lieutenant Denis Bertram Sydney Buxton, son of Sydney Buxton, 1st Earl Buxton, a radical Liberal Party (UK) politician and Governor-General of South Africa.

It was designed by Sir Herbert Baker, with sculptures by Joseph Armitage and Ferdinand Victor Blundstone, who also sculpted part of the Newfoundland National War Memorial.

The memorial was unveiled on 20 June 1927 by Sir Gilbert Dyett.

* Thank you to Wikipedia